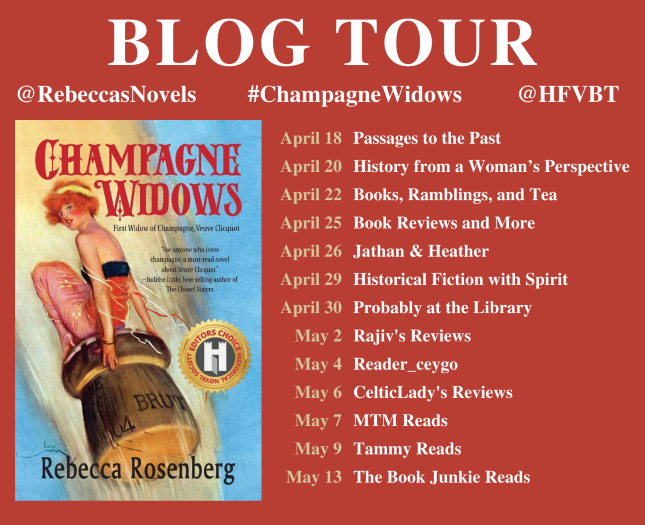

Champagne Widows

by Rebecca Rosenberg

Paperback Publication Date: February 25th 2022

Lion Heart Publishing

Genre: Historical Fiction

Triple-gold-medal-winning author Rebecca Rosenberg serves up a triumphant tale of talent and ambition, love and loss, betrayal and redemption, and accepting yourself and others for who they are.

Champagne, France, 1800

Twenty-year-old Barbe-Nicole has inherited Le Nez (an uncanny sense of smell that makes her picky, persnickety, and particularly perceptive) from her great-grandfather, a renowned champagne maker.

Her parents, however, see Le Nez as a curse and try to marry her off to an unsuspecting suitor. But Barbe-Nicole is determined to use Le Nez to make great champagne. When she learns her childhood sweetheart, François Clicquot, wants to start a winery, she rejects her parents' suitors and marries François despite his mental illness.

The Widow Known as Veuve Clicquot

Soon, Barbe-Nicole Clicquot must cope with her husband's death. Becoming a widow known as Veuve Clicquot, she grapples with a new overbearing partner, the difficulties of making champagne and the Napoleon Codes preventing women from owning a business.

All this while her father takes a military uniform contract from Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, who wages six wars against European monarchs, crippling Veuve Clicquot's ability to sell her champagne.

Challenging Napoleon

Using Le Nez, Veuve Clicquot struggles through unbearable hardships and challenges Napoleon himself. When she falls in love with her sales manager, Louis Bohne, who asks her to marry, she must choose between losing her winery to her husband, as dictated by Napoleon Code or losing Louis. In the ultimate showdown, Veuve Clicquot risks imprisonment and even death as she defies Napoleon.

Available on Amazon

Praise

CHAMPAGNE WIDOWS BY Rebecca Rosenberg

Chapter One

“Champagne. In victory one deserves it, in defeat one needs it.” –Napoleon Bonaparte

1

Le Nez

The Nose

Reims, Champagne, France 1797

Grand-mère sways over the edge of the stone stairs into the cavern, and I step between her and eternity, dizzy from the bloody tang of her head bandage.

“Let’s go back. We’ll come another time.” I try to turn her around, so we don’t tumble into the dark crayère, but she holds firm.

“There won’t be another time if I know your maman and her heretic doctor.”

They drilled into Grand-mère’s skull again for a disease they call hysteria. The hole was supposed to let out evil spirits, but the gruesome treatment hasn’t stopped her sniffing every book, pillow, and candle, trying to capture its essence, agitated that her sense of smell has disappeared.

“This is how you know you are alive, Barbe-Nicole.” She taps her nose frantically. “The aromas of brioche fresh from the oven, lavender water ironed into your clothes, your father’s pipe smoke. You must understand. Time is running out.” Her fingernails claw my arm, the whale oil lamp sputtering and smoking in her other hand.

“Let me lead.” Taking the stinking lantern, I let her grip my shoulders from behind. Grand-mère shrunk so much, she’s my height of five feet, though she’s a step above. For as long as I remember, she has tried to justify my worst fault. My cursed proboscis, as Maman calls my over-sensitive nose, has been a battle between us since I was little. I remember walking with her through town, avoiding chamber pots dumped from windows, horse excrement paving the roads, and factories belching black gases. Excruciating pain surged to my nose, making my eyes water and sending me into sneezing fits. Maman left me standing alone on the street.

From then on, my sense of smell swelled beyond reason. Mostly ordinary odors, but sometimes I imagine I can smell the stink of a lie. Or the perfume of a pure heart. Or the heartbreaking smell of what could have been.

Maman complains my cursed sense of smell makes me too particular, too demanding, and frankly, too peculiar. Decidedly troublesome traits for a daughter she’s tried to marry off since I was sixteen. But why must the suitors she picks have to smell so bad?

Grand-mère squeezes my shoulder. “It is not your fault you are the way you are, Barbe-Nicole; it’s a gift.” She chirped this over and over this afternoon until Maman threatened to have the doctor drill her skull again.

The lantern casts ghoulish shadows on the chalk walls as my bare toes reach for the next stair and the next. I’ll have hell to pay if we’re caught down here. Part of me came tonight to humor Grand-mère, but part of me craves more time with her. I’ve witnessed her tremors, her shuffling feet, her crazy obsessions, which now seem to focus on my nose.

As we descend, the dank air chills my legs; feathery chalk dust makes my feet slip on the steps. The Romans excavated these chalk quarries a thousand years ago, creating a sprawling web of crayères under our ancient town of Reims. What exactly does Grand-mère have in mind bringing me down here? The lantern throws a halo on grape clusters laying on the rough-hewn table.

Ah, she wants to play her sniffing game.

“How did you set this up?” My toes recoil from cold puddles of spring water.

“I’m not dead yet,” she croaks. Taking off her fringed bed shawl, she ties it like a blindfold over my eyes. “Don’t peek.”

“Wouldn’t dare.” I lift a corner of the shawl, and she raps my fingers like the nuns at St.-Pierre-Les-Dames where Maman sent me to school before the Revolution shut down convents.

“Quit lollygagging and breathe deep.” Grand-mère’s knobby fingertips knead below my cheekbones, opening my nasal passages to the mineral smell of chalk, pristine groundwater, oak barrels, the purple aroma of fermenting wine.

But these profound smells can’t stop me fretting about Maman’s determination to marry me off before the year is out. I told her I’d only marry a suitor that smells like springtime. “Men do not smell like that,” she scolded.

But men do. Or one did, anyway. He was conscribed to war several years ago, so he probably doesn’t smell like springtime anymore. His green-sprout smell ruined me for anyone else.

Grand-mère places a bunch of grapes in my hands and brings it to my nose. “What comes to you?”

“The grapes smell like ripening pears and a hint of Hawthorne berry.”

She chortles and replaces the grapes with another bunch. “What about these?”

Drawing the aroma into the top of my palate, I picture gypsies around a campfire, smoky, deep, and complex. “Grilled toast and coffee.”

Her next handful of grapes are sticky and soft, the aroma so robust and delicious, my tongue longs for a taste. “Smells like chocolate-covered cherries.”

Grand-mère wheezes with a rasp and rattle that scares me.

I yank off the blindfold. “Grand-mère?”

“You’re ready.” She slides me a wooden box carved with vineyards and women carrying baskets of grapes on their heads. “Open it.”

Inside lays a gold tastevin, a wine-tasting cup on a long, heavy neck chain.

“Your great Grand-père, Nicolas Ruinart, used this cup to taste wine with the monks at Hautvillers Abbey. Just by smelling the grapes, he could tell you the slope of the hill on which they grew, the exposure to the sun, the minerals in the soil.” She closes her papery eyelids and inhales. “He’d lift his nose to the west and smell the ocean.” She turns. “He’d smell German bratwurst to the northeast.” Her head swivels. “To the south, the perfume of lavender fields in Provence.” Her snaggletooth protrudes when she smiles. “Your great Grand-père was Le Nez.” The Nose. “He passed down his precious gift to you.”

Here she goes again with her crazy notions. “Maman says Le Nez is a curse.”

Grand-mère clucks her tongue. “Your maman didn’t inherit Le Nez, so she doesn’t understand it. It’s a rare and precious gift, smelling the hidden essence of things. I took it for granted, and now it’s gone.” Her wrinkled hand picks up the gold tastevin and christens my nose.

A prickling clusters in my sinuses like a powerful sneeze that won’t release. I wish there were truth to Grand-mère’s ramblings; it would explain so much about my finicky nature.

“You are Le Nez, Barbe-Nicole.” She lifts the chain over my head, and the cup nestles above my breasts. “You must carry on Grand-père Ruinart’s gift.”

“Why haven’t you told me about this until now?”

“Your maman forbid it.” She wags her finger. “But I’m taking matters into my own hands before I die.”

I feel an etching on the bottom of the cup. “Is this an anchor?”

“Ah, yes, the anchor. The anchor symbolizes clarity and courage during chaos and confusion.”

“Chaos and confusion?” Now I know the story is a delusion. “Aren’t those your cat’s names?”

“I have cats?” She stares vacantly into the beyond, and her eerie, foreboding voice echoes through the chamber. “To whom much is given, much is expected.”

Holding her bandaged head, Grand-mère keens incoherently. The lantern casts her monstrous shadow on the crayère wall; her tasting game has become a nightmare.

“Let’s get you back to your room.” I try to walk her to the stairs, but her legs give out. Lifting her bird-like body in my arms, I carry her as she carried me as a child, trying not to topple over into the crayère.

“Promise you’ll carry on Le Nez,” she says, exhaling sentir le sapin, the smell of fir coffins.

My dear Grand-mère is dying in my arms. Now I know Le Nez is a curse.

“Promise me.” Her eyelids flutter and close.

“I won’t let you down, Grand-mère,” I whisper. She feels suddenly light in my arms, but the gold tastevin feels heavy, so very heavy, around my neck.

***

For more information, please visit Rebecca's website and blog. You can also find her on Amazon, BookBub, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Goodreads.

No comments:

Post a Comment